"You get a little bit institutionalised really. You get up the morning and you have a routine, like any job I suppose. You get up and do a similar type of thing each day - I used to try and go in the gym every morning with Glenn (Patterson, player liaison officer), and then we had a meeting, and the day panned out similarly. Very quickly, I've realised that that routine I had, I'm going to have to replace in semi-retirement. In any job, if you just suddenly get off that wheel, you're just looking round, thinking, 'what do I do here?'"

Wright, a fixture like few others at St. James' Park, retired from full time football earlier this month, ending 38 years of service to his team, his club. As head physiotherapist he has treated hundreds of players, been a confidant to many, a friend too. The cord tying him to United is too thick to sever but is it time for something else. This is his first week away from the hum of the training centre and "do you know what? It's actually been sort of hectic, really," he says, neatening a pile of papers. "The reaction I've had from people has been unbelievable. I've had to speak to a lot of people, message a lot of people, and it's been really busy. I said a proper goodbye on Friday, a personal goodbye, which was nice. I think I felt a bit better after that, rather than just disappearing. It was a chance for me to say thank you, and that I'll miss them, really. I felt better after doing that."

After his departure was announced last week, tributes and well-wishes from players past and present tumbled in. They made Wright - the warm, calming beating heart of Newcastle United - "pretty emotional". He is 63 now, father to Jonathan, Benjamin and James and husband to Helen, but to others he is Del, Del Boy, Derek, a bona fide living legend. He can let priorities shift a little now; there will be a family holiday this summer, parents to spend time with, maybe some travelling.

"The boys are desperate for me to go and watch the games, which I'm sure I will," he says. "They're in the family enclosure at the moment and they say I won't be able to make it up the stairs, so I'm going to have to get myself fit to get up those stairs with them.

"It's going to be a new chapter in my life. I've been so fortunate and had a wonderful career. There have been times where it's been stressful or things maybe haven't worked for the club or the team, but you have to keep going. You have to keep ploughing on, no matter what, and that's what I'll do for the rest of my time."

Wright grew up in Stanley, leaving Stanley Grammar School at 16 to join Arsenal as an apprentice. Medicine held a curiosity for him as a teenager - his brother would become a doctor - and during his two years at Highbury he met Fred Street, the former England physio. Wright would ask him questions about his trade ("I think he thought that was a little strange, really,") and eventually Street suggested he became a remedial gymnast. "They used to use remedial gymnasts in the war, to rehabilitate soldiers after injury," he explains. "There was only a small society of them, about 500 members, but I thought it looked ideal."

After he qualified the society fused with the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy, so he trained in that discipline too. His first job was at Northumberland Miners' Rehabilitation Centre at Hartford Hall. "A lot of classes, mining injuries - back injuries, knee injuries. The miners were good, solid people, you know. I was only 18, 19, 20 at the time so I was learning the trade, but they were great to work with as a group."

Some old patients from those days have got in touch with him since the news broke. "God knows how old they are - they must be 99, 100 now," he chuckles. "That was a really great place to work. There was a model mineshaft at Hartford Hall, where you had to take the patients down, rehabilitate them through pushing the wagon, put the pit props up, all that type of thing. It was a good grounding."

But football reeled him back in. He was 23 when Street called with a proposition. Malcolm Macdonald - a star at Arsenal when Wright was trying to make it as a player there - was managing Fulham in the Third Division and needed a physio. "They said, 'well, you've got to be here at half nine tomorrow morning'. I left at half three in the morning, drove down to Fulham, had the interview and they offered me the job straight away.

"I was looking after the first team, the youth team, reserve team. I used to play for the reserves as well when they were short. I took my bag and if anybody got injured, I ran off the field, got the bag, ran back on the field, treated the player, and you could see the other players thinking, 'what the hell is going on here?'"

In 1984, Wright was tempted back to the North East. Dr Keith Beveridge offered him an interview with the Magpies. "It was the night before the 5-5 against QPR on the plastic pitch at Loftus Road," he remembers. "I was in London, and drove over to meet Jack - Jack Charlton - and the doc. They had dinner and I met them after.

"We were just talking, really, just chatting. Jack was talking about fishing quite a bit of the time. He asked me a bit about my background, football, and then Jack just said, 'right, as far as I'm concerned, you've got the job. Would you like to come?' 'Yes'. That was it."

Wright was happy at Fulham and Fulham were happy with him. Ray Harford, Macdonald's successor, wanted to keep him but he'd felt the pull. It was "a bit of wrench leaving Ray. He didn't want me to leave. But he understood it was me going back home."

World Cup winner Charlton and Willie McFaul called the shots at St. James' then. "You could tell you were working for a big club with a big history. But you sort of get sucked in. The feeling straight away of how important it is. But people made me feel welcome.

"The club was, always is and always will be a huge club. But going by facilities, the treatment room and whatever, and it probably wasn't as good or far advanced as I thought it would be. In a way, I thought, 'right, I'm going to take this by the scruff of the neck and try and get a grip of this place', and try and push forward.

"It was a big job, a big club and a big staff, and there were things that were needed facility-wise, just to try and do the job properly. But I got stuck in straight away and just tried to sort out my own treatment room and gym. I like things nice and neat and tidy and it should be in a treatment room - Bobby Robson always used to say, 'it's our hospital, so it needs to be clean'. He was right, really. I got all the apprentices, Gazza and co, to get on with cleaning things and generally spruce the whole place up."

The welcome he received from Glenn Roeder, Kenny Wharton and Peter Beardsley before his first game - a midweek League Cup tie at Ipswich Town - stays with him. Since then Wright has welcomed countless other colleagues to the club. Maybe his experience influenced the kindness he would show when doing that. He disagrees. "I think it's what you are as a human being. It's nothing to do with football. Football is, and can be, a quite intimidating environment. I try and make people feel comfortable. There's nothing worse than seeing somebody feeling uncomfortable or awkward. I don't think that was just me in football. I would like to think that was just me."

To Newcastle supporters of a particular vintage, he is the man with the bag who tore onto the pitch to reach stricken players. "Now, it's more difficult - they've got to wait for the referee - but then you got on as quickly as you could," he smiles. "I always remember just running as quickly as I could, but then I was kind of aware, in the background, of the cheering. I'm thinking, 'did the crowd just cheer me going on the field there? That's a bit strange'. Then I became aware of it. And then, I thought to myself, 'right, Derek, you're going to have to stop racing on the field'. I thought, 'it's childish of me, I shouldn't do it, just concentrate on the job'. But I couldn't help it. Once they started cheering, that was it.

"I was running on once and Darren Peacock actually blocked their physio on his way over! Even the players were getting involved by the end. But the feeling, selfishly, was fantastic. It was a good rapport with the crowd - that was the main thing. That was what I liked. I'm one of them, really, I suppose."

His role changed over the years and Wright rolled with it, adapting to advancements in sports science, in data. He says his intuition, his nous for when a player was fit or not, confident or not, never went. Neither did he. "I probably had the opportunity to leave on a number of occasions," he admits. "I wanted to keep working and keep working here. I couldn't imagine me working at Manchester United or Manchester City. It just didn't appeal to me really. That sounds a bit naff I suppose, but it didn't. The idea was I wanted us, our medical department, to become the best, and no matter how hard it was at times or how difficult it was, I think the department now is fantastic. I'm quite happy and proud of where we eventually got to.

"I think now, with the new owners and new investment, I'm probably leaving at the wrong time. But it's the circle of life. There's a fantastic future coming up here. The facility you'll probably end up getting is different to me trying to de-rust the multigym at Benwell with an oiling can when I first arrived."

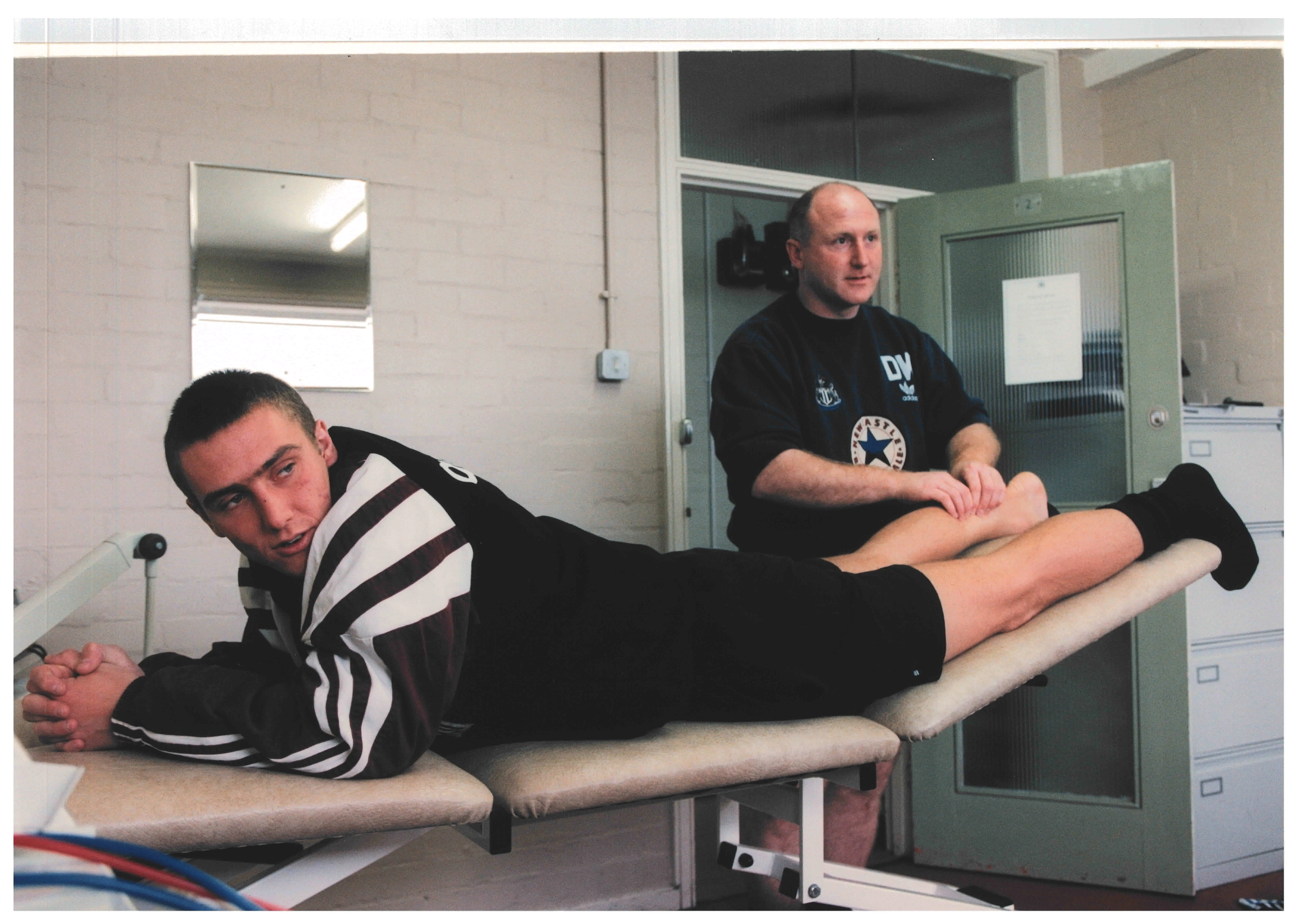

We look through a few old photos which hint at his connection with the players he has helped. Being there when needed, a willing ear, was a side of the job he found "fascinating". The first photo elicits a belly laugh. "Alan Shearer shot me in the head, would you believe, with a paintball, and thought it was very funny," he says. "I'm not sure I did!

"You have to be in a situation where they trust you, and hopefully that's been the case over the years. I think as a physiotherapist - although you were never trained in it, certainly myself - I was very much aware of that side of it and very much aware of if somebody was going through a rough time. They're human beings. You just have to be aware. You have to be a good listener. You have a bond. That's the best word."

Then comes the pictorial evidence of the pink tutu he wore to the players' Christmas fancy dress-themed party, as explained during an interview with The Times in 2018. That one will remain unseen by the masses. "Oh my God. That was the Kevin Keegan era. We were all very, very close. There was only me and Paul (Ferris) as medical staff, but we had a very good bond with the players and the players had a massive bond too. They were very, very close and very successful under Kevin.

"For some bizarre reason, I ended up with a pink fairy outfit with Dr. Martens, and the rest is history. I just remember waving down a taxi at the end of the night with my wand," he shakes his head, with a grin and a giggle. "It didn't work."

There are so many memories - some may even be printable - and it is impossible to do them all justice here. He says he will write some of them down, make sure they aren't lost in a distant corner of the mind. FA Cup finals, Champions League nights, Kevin Keegan, Sir Bobby Robson. "He was lovely, a lovely man. He was from the same neck of the woods as me so we used to have a lot of conversations about Stanley, Langley Park, Southmoor Juniors who we used to play for when we were younger. Conversations with him were great," he says. "Then Kevin and Terry (McDermott), that period of time - that was unbelievable. We never stopped winning.

"And the staff that you work with - Ray Thompson (kit manager) and Tony Toward (team administrator) have been there virtually all the time I've been there. They've lived through everything I've gone through as well, and they're still going. Just really, really good people. And good times."

What is it, then, that has kept him here, all this time? He takes a moment to think. "I think loyalty," he answers. "You do feel as if it's ingrained into your soul, really. It would have been very difficult to leave - it's been difficult to leave now, but it's the right time. I've always wanted to go on and on and on for as long as I could. You think, 'we just might win something this year' - that tends to keep you going. And I think they will - we're not far from that now.

"It's hard to describe. It gets under your skin, it gets into your blood."

He leaves a legendary figure. It is a badge you feel Wright might wear a little uneasily but he appreciates its intention, the meaning of it. "When I looked at some of the messages my boys showed me, it was like, 'wow'. It was very emotional. I'm very honoured, really. It's a lovely feeling. I'm sure there are a lot of people who would honour that sort of tag better than me. But it is a nice feeling when someone calls you that, I can't lie.

"I'm not on social media as such - I'm on LinkedIn, but I never look at it - but there were a lot of lads I worked with at other clubs or knew from when I first started, or first started at Fulham, who sent some lovely messages which I'm going to reply to. I've looked through. Unbelievable, really. I'm so grateful. The boys are quite excited when they see nice messages, I think. I do really appreciate it. I might have to join social media now. You'd have to show me what to do though."

He laughs. It cannot be easy to bookend such a special part of your life. Wright has so much to look back on but there are other things to look forward to now. "I have to try and do that. I have to try and get on with my life now," he says. "But that will never go away - it will always be part of me, and a part which I'm proud and honoured to have done. I'll never forget it. It will always be there. If I can get up all those stairs to the family enclosure, I'll be there with the boys.

"They said to me, 'you'll have to learn all the words to the songs, Dad'. I went, 'I've heard the songs for the last 38 years. I know all the words to them. Don't worry'."