Irving J. Schaffer was born in Amsterdam, New York, in 1918. He was a technical sergeant in the United States Army Air Force. During the Second World War, Schaffer undertook 65 combat missions in a B-25 medium bomber, serving as a radio operator and photographer on board. He kept a secret diary – against military rules – in which he detailed, matter-of-factly, the minutiae of his days in the command: each early rise, each meal, each operation he was part of, each emotion he could make out through what must have been, at times, restless exhaustion.

Schaffer’s diary was published in its entirety in 2005, titled Red Skies at Night. It paints him as a humble man – when presented with a clutch of medals, he describes the honour with disarming modesty – and the reader eventually warms to his tone. As well as an account of his service in southern Europe, the diary serves as something of a love letter to his wife-to-be, Shyrle, who regularly sends mail from back home. He often mentions how much he misses her; he always tried to write back.

After the war, and reunited with Shyrle, Schaffer lived in Boston and St. Louis before moving 1,500 miles south west to Phoenix, Arizona, in 1960. There, he opened the city’s first high-end clothing store, called The Gentry. The couple spent the next 51 years together until Schaffer’s passing, at the age of 93, in 2011. They had 33 great-grandchildren. DeAndre Yedlin is one of them.

Schaffer died when the USA full back was 18, but he remembers him well. He would travel from Phoenix to visit Yedlin and his family in Seattle every year. “My family is quite young, so I was fortunate to be able to meet him and have a good relationship with him and my great-grandmother,” he says. “My mum has actually shown me a picture of me with my great-great grandmother as well. Five generations in one picture. That’s pretty amazing.”

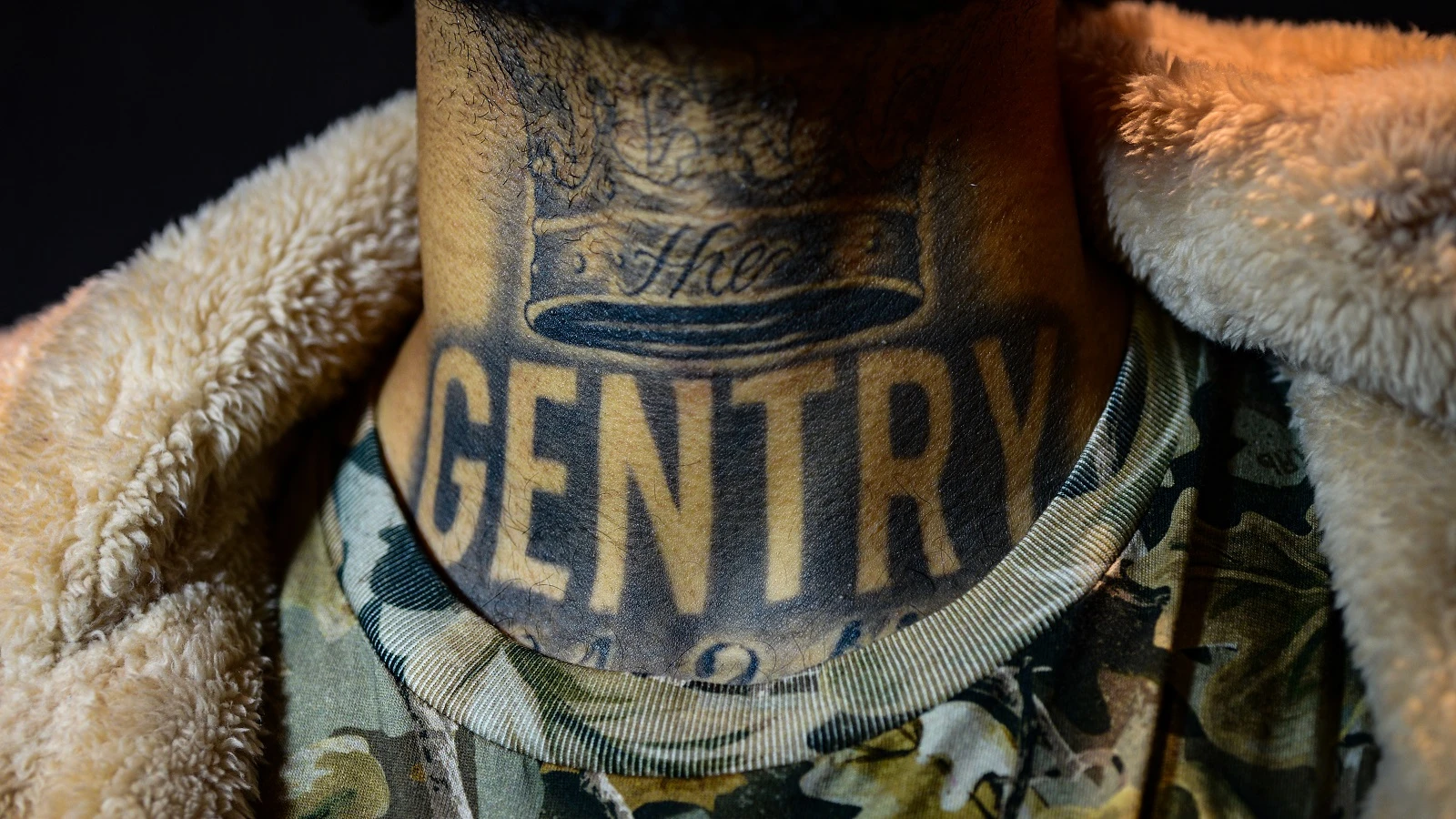

The pair shared a love of fashion. Yedlin knew Schaffer as ‘Poppy’ – he now has a poppy tattooed on his arm in his memory – and, as he speaks, another tattoo pokes out from under the collar of his dark red sweater. The words ‘The Gentry’ are written across the front of his neck in an imposing font, tucked just below his wiry black beard.

“Gentry means royalty, so that’s why I have the crown on top of it,” he explains, tipping his head back slightly. “Even if people look at it and they don’t get it, then at least I know that, to me, it means something. That’s one thing my grandmother told me when I was young before I got tattoos. She said, ‘I don’t care if you get tattoos, but if you do, make sure that every single one you get means something’. A lot of people get them and they don’t mean anything – they just look cool at the time, or it’s a trend. They get to a certain age, and they don’t like it. But at least if you don’t like the way it looks anymore, it will still mean something to you. That was kind of the thought process behind my tattoos – they all have to mean something.”

Yedlin knew his great-grandfather as 'Poppy', and has a poppy tattooed on his right arm in his honour

The interview was arranged primarily to mark the 26-year-old’s 100th appearance for the Magpies, but it is difficult to separate Yedlin the footballer from Yedlin the artistic, colourful fashionista. Almost two years ago he invited this publication to his Jesmond home for an interview in which he changed outfits six times, outlining his plans for his clothing label, Roselle, as his English bulldog Simba scooted around his living room on a skateboard.

But reaching a century of appearances calls for some further introspection, and the 26-year-old is happy to reflect on a few highlights from his three-and-a-half years at the club. Winning the Championship, and thus proving his 2016 move from Spurs was a wise one, is up there, “and beating Manchester City was a good one too,” he adds. “A lot of people had written us off that game. I think it kind of kick-started our second half of last season. And finishing tenth, the year after the Championship – that as well. A lot of people thought that we’d get relegated that season.”

The 2017 title win aside, each of those achievements could be classed as unexpected triumphs. Is there something particularly gratifying in upsetting the odds? “I think so. For whatever reason, this club’s in, I don’t want to say the spotlight, but I get the feeling that people want this club to fail, for some reason,” he says. “I think we can prove them wrong, and it is quite a good feeling – not in the sense that we’re proving them wrong, but proving the fans and supporters that believe in us right. It’s good for them, and for us. We’re not this every-year relegation team that everybody seems to think we are.”

How much of that can you attribute to the team simply adopting a certain mindset? Is that what happens? Or is it something else? “I don’t know – I think that’s more of a bigger picture type thing,” he says. “Each individual game is just about focusing on what’s at hand, the different situations to take care of and the players you have to be wary of, but in terms of feeling like an underdog – that’s more of a bigger picture thing. That’s when you finish a season and look back at what you’ve done and accomplished, that’s when that feeling sets in.

“You can be proud of it. I always say this – people might see us as an underdog, but we’re a confident side. We’re a team that is not going to back down from anybody.”

He finds a question on his lowest point easier to answer. The sports hernia problem which kept him sidelined from the end of last season and the start of the current one was greatly irritating, more than anything. “Mentally, I wasn’t really prepared for it, because I thought the recovery would be a lot quicker than it was,” explains Yedlin. “It ended up with me being out for five months, and it was supposed to be a six to eight-week recovery. I think for anyone, that would take a toll on you.

“Now I’m getting back into things, but I’m still not where I think I need to be. Before my injury, in mostly every game I played, I didn’t have a feeling of being completely finished. But in the couple of games that I’ve come back into, at the end of them I’d just felt completely done. I probably am working a bit more just because of the system and the way Steve Bruce wants me to play, but in terms of fitness I don’t like feeling like I’m completely shot. That’s not how I like to feel.”

Yedlin takes on West Ham's Robert Snodgrass during his 100th appearance for Newcastle United

His absence, some of which coincided with the off-season, made him miss the game and it could be argued, too, that his team missed his boundless energy down the right during parts of that period. Yedlin feels he has improved positionally since he arrived on Tyneside at 23, but knows how that aspect of his game is perceived by some. “People will tell me, ‘you make up for being out of position with your speed’. At times, yeah – but if you think of a basketball player who is seven foot three, is he not going to use his height?” he asks. “So of course I’m going to use my speed in certain situations. There’s definitely situations where I can be in better positions, but speed is probably what I’m known for and it’s going to help me get out of certain situations.”

The idea that his pace masks his weaknesses bothered him more when he was younger. “That’s another thing I’ve learned – to just channel stuff, channel things out,” he says. “It’s a funny one to me. But everyone’s entitled to their opinion. You’re going to have people who don’t think the best of you, and you’re going to have people who think you’re great. That’s fine for me.”

Of the six right backs who have turned out for Newcastle since the summer of 2016, Yedlin has become the most enduring. He says he learned plenty from Vurnon Anita in his first year at the club, observing his calmness and awareness of time, and insists that being open to learning was critical when it came to establishing himself as first choice. “I think when new people come, a lot of players’ thought process is that it’s a threat – that they’re coming in to take your position,” he muses. “Honestly, my thought process is, ‘what can I Iearn from this player? What can I absorb from this player, and use in my game?’

“I think you can learn something from everybody. Even the youngest player on the team, Matty Longstaff – look at him. You can learn things from him. Everybody’s different, and they do things differently.”

"I always say this – people might see us as an underdog, but we’re a confident side. We’re a team that is not going to back down from anybody."

Yedlin’s 100th outing came at West Ham last weekend in the 3-2 victory that seemed to go some way towards recalibrating public thoughts on the quality within Bruce’s side. He is familiar with the fluctuating emotions of the English game now, and the need to keep his own on an even keel during these typically eventful seasons, but it is heartening to learn his involvement in the seclusive world of top-tier sport has not obscured his view of life. He rolls up the right leg of his tracksuit to reveal another tattoo: a portrait of Irving J. Schaffer, inked onto his calf. “He was just always my biggest fan. He was always, always, always interested in what I was doing, even from when I was five years old,” he says. “I know it’s kind of what grandparents and great-grandparents do, but he was. I’ve been around kids and sometimes it’s hard to keep up a conversation with them, but he would be genuinely interested.

“That just kind of shows the love he had for me. And I think just the fact that he was the head of the family, the oldest one, I saw him as almost like this big figure, you know? He always showed love to me, always asked about me and my sister as well. He was just a really great guy.”

Yedlin says he has all of his great-grandfathers medals at home, displayed in a frame. He takes out his iPhone to double-check a detail before relaying one final tale about Schaffer, who dabbled in real estate. It concerns the American baseball player Reggie Jackson, a legend of his sport who – at a time when racism was rife – was struggling to purchase a house. Schaffer, explains his great-grandson, went out of his way to sell him one, and in return Jackson gifted him a signed bat.

His uncle still has the bat. A depiction of Jackson sits just below Schaffer’s image on Yedlin’s leg. “When I heard that story, I kind of just… yeah,” he nods. Pride isn’t always the most perceptible feeling in these kind of interviews, but he looks full of it. “It’s cool just to know that he stood for that, and that he was one of the only ones in that time that did. It was really crazy, really, really crazy. But I’m glad that he was on the right side.”

Yedlin's tattoo of his great-grandfather and, just below it, the image of Reggie Jackson